How genocide can happen on our ordinary streets

Date 16.11.2015

The University’s Father Tim Curtis has recently returned from Bosnia-Herzegovina (a part of the former Republic of Yugoslavia). While there, Father Tim remembered the Srebrenica massacre – the genocidal killing, in July 1995, of more than 8,000 Bosnian people. Here is his story in pictures…

“Bosnia is a beautiful place which is in sharp contrast to the evidence of the conflict which is still very much there. Sarajevo is peppered with bullet holes” Police Chief Superintendent Gavin Thomas

Great civilisations don’t clash, they ebb and flow. At the boundaries of the great civilisations of global history, little pockets of people from different cultures and mind-sets get mixed up and isolated from their mother culture. Enclaves and ghettos develop and the people, even though they live for hundreds of years next to each other; their separate histories are kept raw and alive, ready to burst into open conflict at any time.

I have had the privilege of visiting three countries in the space of three weeks, first Bosnia-Herzegovina (a part of the former Republic of Yugoslavia), then Turkey and then to greenest Vermont in the USA, perhaps the most monocultural and homogonenous states in the USA. It is the nature of the civil war in Yugoslavia, and the acts of genocide in Srebenica that I want to focus on, but the counterpoints to this are the current situation in Turkey, in homogenous communities like those in Vermont and the sorts of communities I meet in my religious, parish life and those I meet in my University based work on public safety and crime.

In one sentence, I have connected genocide and the atrocity of civil war to Christian parishes and student life. This is rather scandalous, but my thesis here is that genocide is banal, brutally banal and liable to happen within the most ordinary of people.

After the death of Tito, the rule of the socialist state of Yugoslavia, the unfinished business of the Second World War erupted again. A complex mix of Serbian retaliation to the genocide by the Croats in the 1940s, the separatist instincts of the Croats and Slovenes, the survivalist strategies of the Macedonians and the territorial ambitions of the Bosnians all collapsed into a conflict that was waged on multiple fronts from 1990 for five years. As a University student at the time, my understanding of the war, before the days of social media and constant TV footage, my grasp of the issues were minimal and even now, 20 years later the whole story is impossible to describe neatly and without offending at least one side in the conflict. Even the detailed and forensic BBC documentary of the time has encountered difficulties in getting the story right.

I went to Bosnia with a vague memory of the music and ice-dance of Torvill and Dean’s Bolero and the memory of my friend and best man, Fr Matthew Goddard going to the region in an old army landrover ambulance to help, and with friends and colleagues from Police forces in the UK and teachers from primary and secondary schools. We were responding to an invite by a British charity Remembering Srebrenica to visit Sarajevo to learn about the siege and to the small town of Srebrenica to learn about the acts of genocide committed there, in which over 8,000 people of Muslim and Bosnian background were brutally murdered in a variety of locations by the Serbian nationalist and renegade forces under the military leadership of Ratko Mladic, and then whose remains were later dug up and scattered in new hiding places across the countryside to hide the evidence. Thousands of innocents were brutalised, killed and murdered on every side. 8,000 people is a huge number, but even more so is the estimated 500,000 Serbs killed by Croats between 1941-45 and (I am writing this on the memorial day for the opening of Auschwitz) the 1,100,000 people killed in one concentration camp alone.

With the imposition of socialism by Josip Tito in Yugoslavia after the Second World War, the Cold War froze the sectarian divides. The seven nations were comprised of the overlap of three great civilisations. Downtown Sarajevo is a perfect example of this overlap, with the Ottoman architecture stopping suddenly to give way to the Austro-Hungarian, but with the Orthodox Christian and Jewish communities living in and amongst each other. Nationality, ethnicity and religion get all mixed up, but dictatorship, no matter how benevolent, suppressed but did not resolve the conflicts that even had a name ‘balkanisation‘.

Once Tito was gone, the overarching sense of there being a unity more important than ethnicity, religion or even tribe was gone and the region descended into conflict. The bits of the conflict I saw on my visit this June 2015 were in Sarajevo, the scene of the longest military siege in modern history in which the whole city was surrounded entirely by hostile forces, that even extended into a part of the city from the surrounding hillsides. The city was even further cut off from the Bosnian army supporting the residents of Sarajevo by the United Nations controlling the airport. Such was the nature of this ‘safe zone’ created by the United Nations that Sarajevo was cut off from the help and arms it needed. A tunnel was built under the airport to supply the city still populated by Sarajevans from all different ethnic and religious backgrounds. From the hillsides General Dragomir Milošević bombed and sniped over 5,000 civilians and irregular soldiers, even offering tourist vouchers to foreign nationals to visit the city to take pot-shots at the trapped civilians. The Russian avant-garde writer Limonov was caught on camera indulging in this “enjoyable sport“.

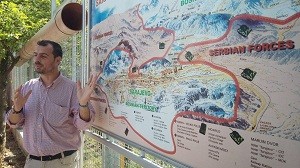

From the siege of Sarajevo we were taken north to the border of the Republic of Serbia (remember that the Serbian loyalist faction were fighting to create what would be called the Republic of Srpska within the boundaries of Yugoslavia) to the mining town of Srebrenica, which had been Serbian five times, Bosnian four times, and Ottoman three times over its history. Here the refugee Bosnians from across the Srpska territory gathered from the 296 villages destroyed by the advancing Srpska army. The region again is creator of a term that echoes across global conflicts now: ethnic cleansing. Srebenica exploded from 5,000 to 50 to 60 thousand people. General Mladić set about starving the population in 1992 having already destroyed the power and water infrastructure. In April 1993 the UN declared the town a ‘safe zone’ but with only 600 ground troops in place while the Bosniak and Srpskan forces both manipulated the situation for their own military gain. By 11th Jul 1995, the Bosnian Serb forces (the Srpskans) walked into an unprotected Srebenica.

The scene shifts down the hill about a mile to Potocari where 20-25 thousand refugees were being contained in and around a derelict battery factory. In a couple of days 2-30 men were killed by the Srpska soldiers, women were raped and children and babies murdered while the inexperienced and overwhelmed Dutch UN soldiers looked on. Women and children were loaded onto buses and forced out to Bosniak held territory but men and boys were separated. Many thousands of the men left behind headed into the hills in an attempt to get to the Bosniak territory but were ambushed and killed. When the column of men collapsed in the fighting the corridor between Potocari and safety in Tuzla was closed. The remaining men and boys were subjected to a planned and systematic slaughter. Thousands were taken to several different remote sites and shot. I watched the films made by the soldiers themselves as they made the prisoners lift dead bodies into trucks before being shot themselves. By Aug 1995, the Srpskan army, presumably helped by civilians, commandeered tractors, diggers and trucks to dig up the buried corpses in bulk and redistribute them to different sites in an attempt to hide the evidence. The size of the operation meant that over 25,000 people were involved in the massacre and the clear up. DNA testing techniques designed especially during the post-conflict investigations established that one body had been scattered over seven different locations.

This is a very partial and incomplete summary of the 5 years of conflict that I was introduced to in a few days. I am by no means an expert in this conflict and much of the detail is still fought over by both sides. The International Criminal Tribunal found Mladic and the President of the Bosnian Serbs Radovan Karadžić guilty of the atrocities and cited the term ‘acts of genocide’. 20 judges from around the world sit on that Tribunal, and yet my own Serbian contacts say that the tribunal only saw what it was given and that it didn’t apply any law that Serbs recognise. In other words, its process and conclusions are still deeply contested. What all sides agree on is that killings and atrocities occurred on all sides.

Whether the events in Srebrenica were atrocities or genocide is a legal and political decision. Clearly the difference is important. A genocide seeks to wipe out a whole people. My impression was that, in letting the women leave Srebrenica, the Srpskans were really focussed on destroying any future resistance movement amongst the men. More profoundly problematic was the size of the killings and the subsequent cover up.

This brings me back to the banality of the atrocities. In 2007, a Serbian court convicted members of the Scorpion unit for some of the more atrocious murders. The film they made themselves of the murders was preceded by the unit being blessed by an Orthodox Christian priest, hopefully unaware of what they were about to do. To organise for the transport, killing and burial of 8,000 people in anything more than a battlefield required thousands of people to arrange for buildings to be available, to identify locations, to hire or commandeer vehicles, to relay instructions; and to repeat it all again months later to hide the evidence. Whilst a few people might be as individually cruel and evil as to rape and murder, the industrial scale of this scale of killing requires something else- the complete dehumanisation of a people. Hearing the stories and watching the eyewitness films of the time gave me a strong sense of the ordinariness of those involved. These were not highly trained killers or brutalised young people, but next door neighbours, cousins and colleagues killing and being killed by each other. Little histories fit into big history, hundreds of small gripes, fights and feuds over hundreds of years remain a bloody part of the present. Every act is symbolic of a bigger feud. Every small gesture reinforces the separation between people. Great civilisations like the Muslim Ottomans, the Roman Catholic Austro-Hungarians and the Orthodox Christian Slavs overlap and sweep forward and backwards over this region in ways that the UK and Vermont can’t really imagine, but the contemporary fulcrum between Europe and Asia, the city of Istanbul does. These civilisations leave behind tiny enclaves of separation as they recede, which the sands of memory chafe and blister.

It’s these memories, these feuds and histories that have to be stopped. The Sarajevan’s I listened to said that the facts of this history had to be agreed and accepted, whilst the Serbs I contacted after the visit were barely in a mood to consider it a civil war, let alone a ‘genocide’. ‘We can’t move on until the facts are agreed’ I was told. I disagree. We will fight over the facts of history forever. The only way forward, the only route to forgiveness and peace, is to stop raking over the history and to look forward to unity. When we can begin to see what a future together should look like, we can then begin to build the structures and the stories needed to live that future. The Christians have a word for this: eschatology. Formally, this is the study of the end-times, but I prefer to think of this as being future-focussed. A positive and stubborn effort should be focussed not on the faults of each other, but on the possibility of living with each other. A quote from the visitors’ book at the Srebrenica Memorial, written the same day we visited, read simply “NEVER FORGET. NEVER FORGIVE”. Actually, we need to begin to forget in order to begin to forgive.

This is not just for Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Republic of Srpksa, two separate peoples joined by a single umbilical cord of Brcka. This future oriented history making is also for communities here in the UK that are riven by ethnic, cultural and class divides. My work on developing Locally Identified Solutions and Practices in community policing may seem tame, but at its heart is the same effort- trying to create a positive and commonly held vision of peace and safety within our most vulnerable communities. Remember that anti-social behaviour is only really a symptom of deeper and more dangerous divisions in our neighbourhoods.

—

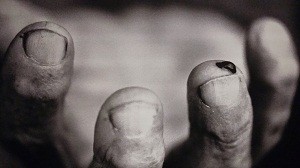

Lead image: Blood taken to extract DNA to identify a victim. From an exhibition by Tarik Samarah.